In 2018, I had the chance to participate in a workshop on archaeogenetics and the media and popular reception of the Viking Age in modern society. This happened in the fantastic historical town of Sigtuna, Sweden.

Along with delighting in the occasion itself, I seized the day to check out the museum along with the townscape which maintains middle ages streets, numerous messed up middle ages churches and a huge selection of 11th-century Viking-period rune-stones. These all benefit the critical visitor’s attention.

Yet, for this blog-post, I want to report here on a less-visited rune-stone compared to those in the town itself. One morning I opted for a go out of town along the lakeside and I looked for one separated runestone to the north-east near Vibyvägen.

This one specific runestone is not extraordinary in any regard, yet its reasonably separated and modest place and its sculpting on an earthfast stone assists me to truly value how these monoliths run in relation to movement and social memory in the early middle ages landscape.

Let me present U412.

This is tape-recorded in the Runor information here.

And its heritage record on Fornsok here

The Runor database translation is:

Sibbi had the runes sculpted in memory of Órœkja, his dad; and Þyrvé in memory of her husbandman.

The engraving on the heritage board checks out:

Sibbi had actually the runes cut in memory of Orökja, his dad and Tyrve/Tyre in memory of her partner.

This is absolutely nothing specific unique– among numerous Uppland rune-stones dating to the 11th century. The basic formula of 2 relative honoring their father/husband mentions the function of these monoliths to honor the dead and assert claims of inheritance over their land and resources.

What is more intriguing is how this earthfast stone permits us to be positive relating to how the monolith had actually initially been positioned, given that it stays in its initial place. So, let us now rely on the materiality and place of the monolith. The heritage analysis panel helpfully describes that:

‘ when the runes were sculpted the waterside reaches nearly to the stone and the roadway from the town of Sigtuna passed it to a landing-stage for ferryboats to Garnsviken. On the opposite coast the remains of a landing-stage can be seen and from there the roadway continued eastwards passing the runestones U411 and U410 and continuing towards Märsta where it gotten in touch with the primary roadway southwards to Stockholm’.

The contemporary roadway– 263– changes this historical interaction path to the north, crossing Garnsviken on a considerable bridge, however in the Viking Age the inlet was much broader and the water level greater.

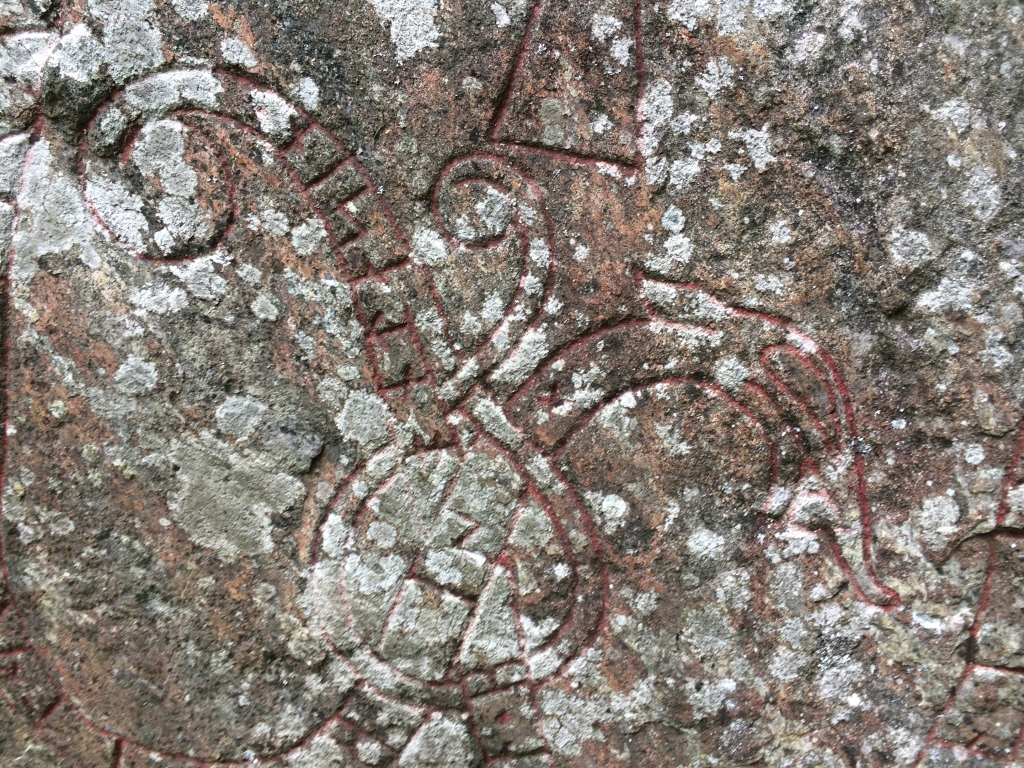

The faded red paint of the runestone is undoubtedly contemporary, to assist visitors and residents alike value the mnument which may otherwise be near undetectable. In the Viking Age, it is possible these were sculpted and painted in a series of striking colours consisting of black, white, blue, yellow, red and green.

The engraving in the stone is of a snake connected to itself with the runes sculpted upon its body: a rather normal and basic style for late Viking middle Sweden. A cross is suspended (and I state suspended given that a lot of the crosses may well replicate portable products spent time the next or from clothes) from the animal’s body. In regards to materiality, what is visible about this therefore numerous other 11th-century rune-stones is how the decoration is thoroughly organized to fit the natural stone-shape.

The place is noticeably basic and links to the arguments of Dr Ing-Marie Back Danielsson (2015: 68) relating to how these monoliths run in social remembrance. Rune-stones are not just connected with burial premises and borders, however by both land and water paths. In this circumstances, we have actually a rune-stone positioned at an essential crossway point– both a pinch-point and an embarkation/landing phase in between land and water. In her argument, Back Danielsson utilizes the example of U112 in the parish of Ed, Uppland to stress how the style of runestones communicates with specific earthfast rock surface areas and this assists to promote the interaction with those going by. At that place there are 2 engravings are on opposing faces of a stone located on a course next to the edge of a lake. Each engraving she argues is developed to fit the stone and to deal with the tourist and engage with how they move close to the stone.

This is however one method which rune-stones have product impact on those moving through the landscape, interaction through multi-media– images and text selected in plain colours on the rocks and set up stones of the landscape. The option of a natural stone is not practical or incidental, I would compete it boosts the connection in between memorial, its topics of celebration, and the location where they are celebrated. In this style, to move would be to keep in mind– to be triggered to engage with the names of the dead and declares to land and resources by their enduring kin.

Taking this point of view on U412, we can see how its portal-like development of the vertical stone surface area and surrounding snake upon a natural stone looking downslope over the water, the striking style of snake with runic text upon its body, and the suspended cross as an expression of faith however likewise of security, challenges visitors showing up over inlet and moving onwards towards the Viking town. Also, those leaving over water would have this monolith to their backs, noticeably noticeable when newly painted throughout the narrow inlet.

Here is the historical picture of the rune from the Runar database which even more stresses how, when clearly coloured in red or white or other mixes of colours, this stone would make up a striking function of the paths towards among middle Sweden’s essential late Viking-Age settlements.

While far from special, this runestone, protected in its initial place, shows the close connection in between the orientation and positioning of runic engravings and their landscape context as important to how they ran to make up social memories through connection to paths of motion. Memory was developed through movement in the Viking Age landscape.

And lastly we concern the heritage measurement. While no longer a primary path of motion through the Swedish landscape, a forest path from the close-by domestic side-road brought me to the rune-stone with a common finger-post directing me the method. Offered the reflections above, more than simply directing heritage travelers, exists a much deeper parallel in between this signpost and the rune-stone itself?

Referrals

Back Danielsson, I-M. 2015. Strolling down memory lane: rune-stones as mnemonic representatives in the landcapes of late Viking-Age Scandinavia, in H. Williams, J. Kirton & & M. Gondek (eds) Early Middle Ages Stone Monoliths: Materiality, Bio, Landscape. Woodbridge: Boydell, pp. 62-86.

Source link