Vindolanda’s Archaeodeath

I sketch here the Archaeodeath measurements of Vindolanda.

This blog site has to do with the archaeology and heritage of death and memory and I want to close my contributions to 2022 by attending to how a popular effective heritage website consisting of ruins of a premiere Roman military historical site, continuous summer season excavations, ‘Roman’ gardens and a museum, offer a heritage tourist environment for checking out elements of death and memory, both in concerns to the human past and our modern environment.

I likewise pick Vindolanda given that it speaks with my most current modified book: The General Public Archaeology of Treasure considered that the website pitches its world-famous tablets as ‘The house of “Britain’s leading treasure”‘. As such, Vindolanda is a ‘treasure’ and includes ‘treasures’, here made use of constructively and favorably to explain indispensable historical finds and their historical contexts instead of commodified loot.

This sketch intends to reveal the numerous different designated and less created styles in which the Vindolanda visitor experience not just clarifies life and times on the Roman frontier through an abundant series of historical finds, however likewise how the website is framed around (a) death, burial and celebration in the Roman military zone and (b) the celebration of the Birley household who have, over numerous generations, examined this historical site. There is likewise a measurement by which visitors can honor through gifting contributions to the website.

Photos were taken in the summer season of 2022.

First Off, we have the general experience of the fort, and the downloadable app motivating visitors to check out ‘the missing out on dead’ (I didn’t download this and utilize it, so I’m unsure just how much mortuary archaeology is included in it).

The Outdoors– Mausolea and Possible Burial Places

There are traces of funerary architectures outside, even if they aren’t firmly determined as either temples or mausolea in each and every case. The prospective status as ‘burial places’ appears to originate from the absence of associated altars. On the indication ‘The town and fort’ reference is made that the visitor is ‘standing near a limit in between the living and the dead, as behind you the primary cemeteries continue down to the roadway towards the next fort. Cemeteries were put far enough far from where individuals lived and worked to prevent the spread of illness or the contamination of the water system.’ While properly explaining Roman-period customs of cemetery positioning, this is quite the imposition of a Victorian public health ideology onto ancient societies. On the other hand, on the ‘Mauseolea’ sign it specifies that ‘Keeping in mind the dead was an essential Roman faith’ which popular burial places were an ‘effectivfe method’ of accomplishing this. It likewise specifies it protested ‘Roman law to bury the dead inside the walls of a town’ which burial places and mausolea were put ‘together with buy roadways leading in and out of the settlement’.

We likewise have the significant location of the discovery of a 3rd-century kid’s tomb was found. The remains will be seen within the museum. Discovered in the summer season of 2010, the indication specifies that the kid was 9-10 years of ages and was interred in an ‘unmarked tomb’ dug through the barrack space flooring in the corner after c. advertisement 213 and prior to the middle of the 3rd century. No description is ventured for this practice.

The Roman Garden

So the historical displays of ruins and traces outdoors mark elements of the Roman cemeteries around the fort and settlement in addition to an enigmatic kid tomb within the settlement. So whilst mainly a heritage website exposing an essential military settlement dating from prior to and throughout making use of Hadrian’s Wall, this is likewise an area to experience and find out about Roman death methods.

To these aspects, we can likewise think about the mortuary measurements of the Roman Garden listed below the historical site and near the museum. Here we experience a little ‘Roman cemetery’ with 4 tombstones of people understood to have actually lived at Vindolanda. It lies next to the course to the Gardens, with an analysis panel discussing them. It is approximated there are 20,000 burials around the fort and elements of Roman beliefs and practices surrounding death are described. The low typical age of death tape-recorded on tombstones is kept in mind, with funeral services performed to ‘perpetuate their memory’. Burial slubs with memberships to make sure a correct burial are likewise pointed out, although the proof of this from Vindolanda isn’t laid out. Listed below, translations of each of the reproduction tombstones are consisted of with descriptions for their terms and material. This in itself is an important environment for interacting the individual relationships and social identities articulated through the epigraphic custom of funerary monoliths from Roman Britain.

On the course in between the fort and the museum is something various once again, a contemporary military monolith. It echoes 20th-century war memorial designs, however this time the monolith is ‘in memory of the soldiers who served Rome on the frontier at Vindolanda, ADVERTISEMENT 85-400’, noting their legions plus ‘and others unidentified’ to cover all bases. On top of the memorial is a royal eagle. The called and unnamed soldiers of the Roman armed force are being celebrated together through this modern-day cenotaph.

Through heritage analysis, these aspects inform and honor the Roman past, however joining them are measurements of ‘meta-commemoration’ by which I indicate the celebration of the website itself and its history of detectives. In addition to reproduction Roman altars and a turning point, initially, there is a description of the history of the Chesterholm Museum itself as part of the Clayton Estate and the work of Eric and Robin Birley.

Then there are the real memorials themselves in popular positions in between the museum and the reproduction temple and education structures throughout the stream. There is a low curving headstone stimulating a piece of a wheel. One side managing the name of Margaret Birley (1910-2000) (the downlsope side), the opposite (upslope) to Eric Birley (1906-1995). It is appropriate that the medium stimulates a piece of a Roman architecture sculpture– a memorial as spolia.

Nearby, Robin Birley is celebrated a hollow iron sphere bearing texts embodying the popular Vindolanda tablets. A plaque describes the sculpture as a ‘fire ball’ which ‘commemorates the work of archaeologist Robin Birley who directed the Vindolanda Turst and its excavations from 1970-2001, and to commemorate his unbelievable discover, in 1992, of over 350 Roman ink on wood composing tablets (letters) on a Roman bonfire here at Vindolanda’. It goes on to describe the discvoery and to identify the designer and developer Andy Gage, and how it portrays the cursive Roman writing from the tablets. Substantially, it describes how this is more than a memorial sculpture, it is essential to a yearly routine: ‘The fire ball will be ceremoniously lit every year to honor the discvoery of what is now thought about to be ‘Britain’s Leading Treasure’. So this art celebrates both an archaeologist and a ‘treasure’, an interactive monolith utilized in yearly routines of discovery-remembrance.

While not situated in the Roman Garden, it is maybe proper to discuss here the Robin Birley Archaeology Centre as an additional memorial commitment within these landscape.

The Museum

Up until now we have actually thought about the outside measurements to the archaeology on screen, its heritage analysis, and the celebration of the Birleys which offer archaeodeath measurements to Vindolanda. Then, when we get in the museum itself, there are much more mortuary measurements than one may anticipate. As soon as once again, these are much more various than one may anticipate at a website primarily concentrated on the traces of Roman settlement. Yet the mortuary and memorial measurements connect to both the Roman-period archaeology exposed and to the history of the website’s examination.

I here concentrate on 6 essential numerous measurements of the exhibit.

First Off, and a lot of straightforwardly, the ‘life and death on the frontier’ screens of tombstones– that of an unidentified woman and a piece of a tombstone ‘to the spirits of the left’ for Ingenuus who lived 24 years.

There is likewise recommendation to the 1889 discovery of a stone at Vindolanda engraved to BRIGOMAGLOS which is required that of a ‘Celtic Christian’ guy and hence potentially dating to the sub-Roman (5th-6th century duration) according to the text panel (this stone is on screen at Chesters). This is matched to more traces of a possible church and engravings meaning sub-Roman Christian life at the website.

I admit I did not assiduously inspect to see if any of the lots of abundant artefacts on screen originate from mortuary contexts.

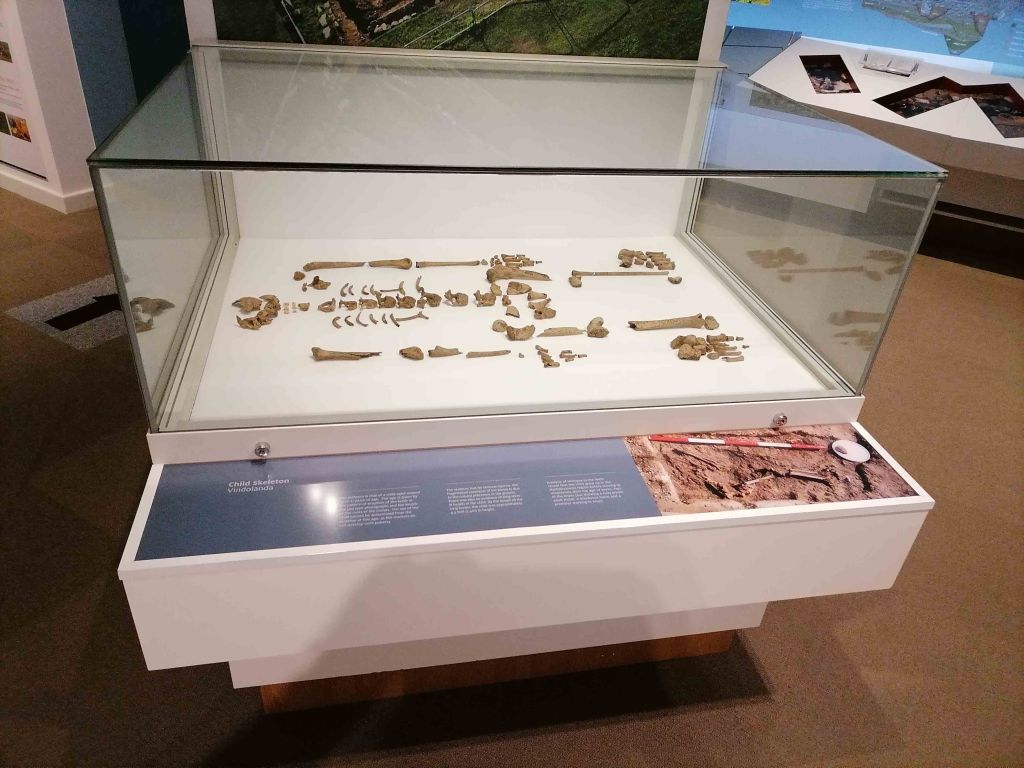

2nd, we fulfill the kid’s tomb which was found within the fort. The bones are set out on plain white with an excavation photo and text panel nearby. The panel does not rather match the external indication, for here the age is put at 10-11 (instead of 9-10). We discover there were ‘no apparent injuries’ or ‘illness’ over the long term, which the kid was 4-5 feet high. Isotope analysis exposes the kid matured in the Mediterranean prior to relocating to Vindolanda c. age 7. Absolutely nothing is stated of the uncommon option to inter the kid within the barrack block.

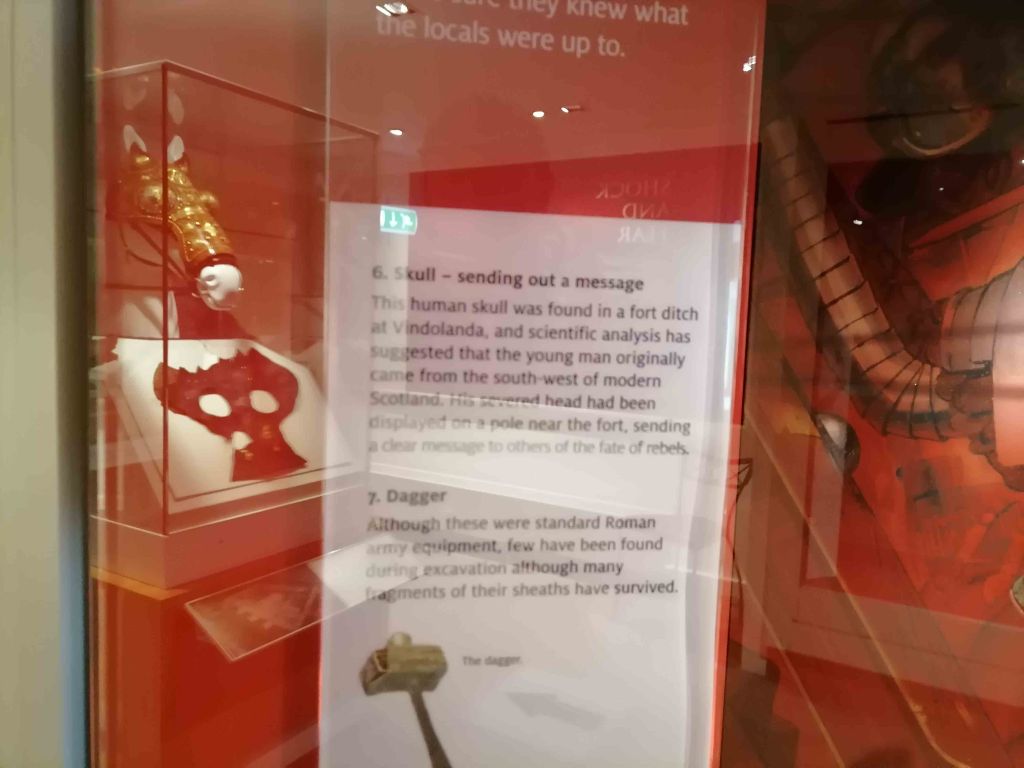

A 3rd more mortuary measurement to the displays is the skull discovered within the fort under the heading ‘Skull– sending a message’. Initially originating from south-west Scotland based upon ‘clinical analysis’, ‘[h] is head had actually been shown on a pole near the forst, sending out a clear message to others of the fate of rebels’. Especially, the Roman Army Museum (likewise run by the Vindolanda Trust) offers an alternative view. It even more describes that in 2002 the excavations at Vindolanda discovered ‘a severed human head at the bottom of the ditch’. He had actually suffered a ‘ruthless death’ with one side of his skull sliced open by spear or sword, the opposite slammed by a blunt instrument. Consequently his head had actually been shown ‘on a pike’. In 2015, aDNA analysis recommended that he had ‘Italian DNA’. Instead of a regional Briton, although he matured in your area he might have been ‘Roman’. The panel provides with the reasoning ‘his further was born in Italy so it would appear that life on the frontier was more complex than an easy ‘us’ and ‘them’ or Roman and Barbarian almost 1800 years ago’.

4th, the Birley household are themselves celebrated together with other leaders of examining the website of Vindolanda, matching the outside memorial aspects currently pointed out.

5th and lastly, the museum itself is a memorial area for visitors: the 2 ‘Sponsor a Leaf’ ‘trees’ on either side of the exhibit gallery enable each leaf to consist of a memorial message from the living to the living and to the dead. Several leaves are clearly ‘for the dead’ by consisting of the expression ‘in caring memory’/’ in memory of’.

Somewhere else on this blog site I have actually assessed the principles of showing animal stays in museums. So, 6th and finally, we fulfill the animal dead of the fort through animal bones on screen, consisting of sheep, goat, livestock and horse in addition to pet. These consist of a concentrate on skulls, however there is an articulated pet skeleton. Paws of different animals are likewise maintained in the tiles on screen.

My function of assembling this article is to demonstrate how, while seemingly a historical site concentrated on proof of life on the Roman frontier zone, there are numerous archaeodeath measurements. Multi-faceted and interleaving, Vindolanda includes rather a good deal of proof notifying us about human death within its screens, enhanced by the screen of animal stays. I would compete there is significant capacity for making use of these resources to inform the story of Roman mindsets and practices surrounding death through extra short-term screens and ‘death tracks’ that connect these measurements in informing the story of Roman death methods. There is more capacity for reviewing contemporary heritage arguments relating to the principles and finest practices of showing and talking about mortuary stays. Additionally, I was struck by the ‘meta-commemoration’ of the website itself, its detectives and its ‘leading treasure’ through museum screens and sculpture, and by the chances for visitors to be memorialised within the museum.

Source link